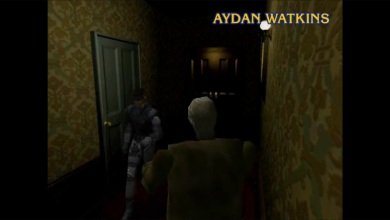

Story Highlights For the longest time, Japanese game design used to live in a little stylish box labeled “quirky,” “hard,” or “incomprehensible anime noise.” But then, Capcom came along and kicked the box down a flight of flaming stairs. Through franchises like Street Fighter, Resident Evil, Devil May Cry, and Monster Hunter, Capcom didn’t just define what Japanese games could be—they redefined what gamers expected globally. The wild part? They didn’t even try to westernize. They just did their weird, brilliant thing – big swords, haunted mansions, melodrama at volume 12 – and the world eventually caught up. Let’s start with Resident Evil. Originally a love letter to B-horror and jump-scares, it taught global audiences that Japanese games could be cinematic, terrifying, and deeply resource-starved. Inventory management became a survival mechanic, not just a UI screen. And Resident Evil 4 practically rewrote the third-person shooter genre while Leon was flipping over tables and saying dumb one-liners in cargo pants. Meanwhile, Street Fighter punched its way into arcades worldwide and basically birthed the competitive fighting game scene. Suddenly, “Hadouken” was a household word. Capcom didn’t just export a game – it exported an entire culture of competition, quarters, and salty rivalries. Why is Street figther more popular than Tekken? But perhaps the most fascinating franchise in this global conquest saga is Monster Hunter – a series that was wildly successful in Japan while being largely ignored in the West for years. It was too grindy, too menu-heavy, too… unapologetically Japanese. Then came Monster Hunter: World, the moment when Capcom opened the gates and let the rest of us in. Streamlined systems, bigger maps, co-op without spreadsheets – and just like that, millions of new players were screaming about turf wars and slicing dinosaur tails with a sword bigger than their own body. That game didn’t just sell well. The Monster Hunter World PC key converted people. There’s no single definition of “Japanese game design,” but Capcom’s version tends to include a few telltale traits: tight mechanical systems, a focus on player expression through skill, bold visual style, and a complete lack of interest in explaining anything upfront. Capcom games aren’t built around what you think you want. They’re built around what will feel good after you get your ass handed to you twelve times and finally understand what that weird item in your inventory actually does. This design ethos – of challenge, style, and depth – has gone from niche to universal. Western studios now borrow from Capcom’s playbook. And players around the world crave that dopamine spike that comes not from cutscenes, but from conquering systems. Capcom didn’t just get lucky with a few hits. They laid the groundwork for global acceptance of Japanese design language. Their franchises showed that games don’t have to flatten themselves to be understood. They can be proudly weird, system-heavy, occasionally nonsensical – and still be iconic. Whether it’s parrying demons in DMC, suplexing villagers in Resident Evil 4, or hunting a screaming wyvern with a musical instrument in Monster Hunter, Capcom’s design DNA is now embedded in global gaming culture. Without Capcom’s takeover and creativity, the eastern gaming development sphere would’ve likely still faced a reductionist critique. Not only did they create great games, each with a unique identity and selling factor, but they also set the stage for other studios in the region to follow. Want to understand why Capcom’s design philosophy hits differently? Start with the global gateway drug: Monster Hunter World. It’s still one of the best examples of how Capcom fused Japanese depth with global approachability. Thanks! Do share your feedback with us. ⚡ How can we make this post better? Your help would be appreciated. ✍

Capcom As A Cultural Translator (But Louder, And With Guns)

byu/Maixell inFightersThe Thing That Makes It “Japanese”

Takeaway

Did you find this helpful? Leave feedback below.

Summary