Story Highlights

- The video game industry has evolved significantly over the past few decades.

- Many new developers have become inspired to create titles, thanks to games like Noctropolis.

- We interviewed Brent Erickson, a veteran game developer, to get his insights into the current industry.

Video games have become an extremely popular form of media, especially in the last few decades. Surprisingly, this sprawling industry is still pretty young, as it only bloomed in the late 1970s and early 1980s thanks to the birth of arcade games. The notion evolved exponentially since then and is even reported to be bigger than Hollywood and the music industry combined.

One of the few people who started video game development following the industry’s inception is Brent Erickson. He has published over 80 titles, some of which were in collaboration with notable companies like EA, SEGA, etc. Brent is also the founder of Flashpoint Productions, which was later sold to Bethesda Softworks in the mid-90s, after which he became the Development Director at Bethesda.

Taking this opportunity, we spoke with Brent Erickson over an email interview, discussing his early years in the industry and his time with Bethesda. Read ahead for the full conversation.

Erickson: I started writing games in 1978 on a TRS Model I. I was 12 at the time. I spent the next 25 years writing games for various publishers like Access Software, EA, and Sega. I’ve also spent about 10 years writing professional automotive simulations and another 10 in professional audio software. I currently work for Harman International (Samsung) in their automotive group as a Distinguished Engineer.

As far as my ventures in games:

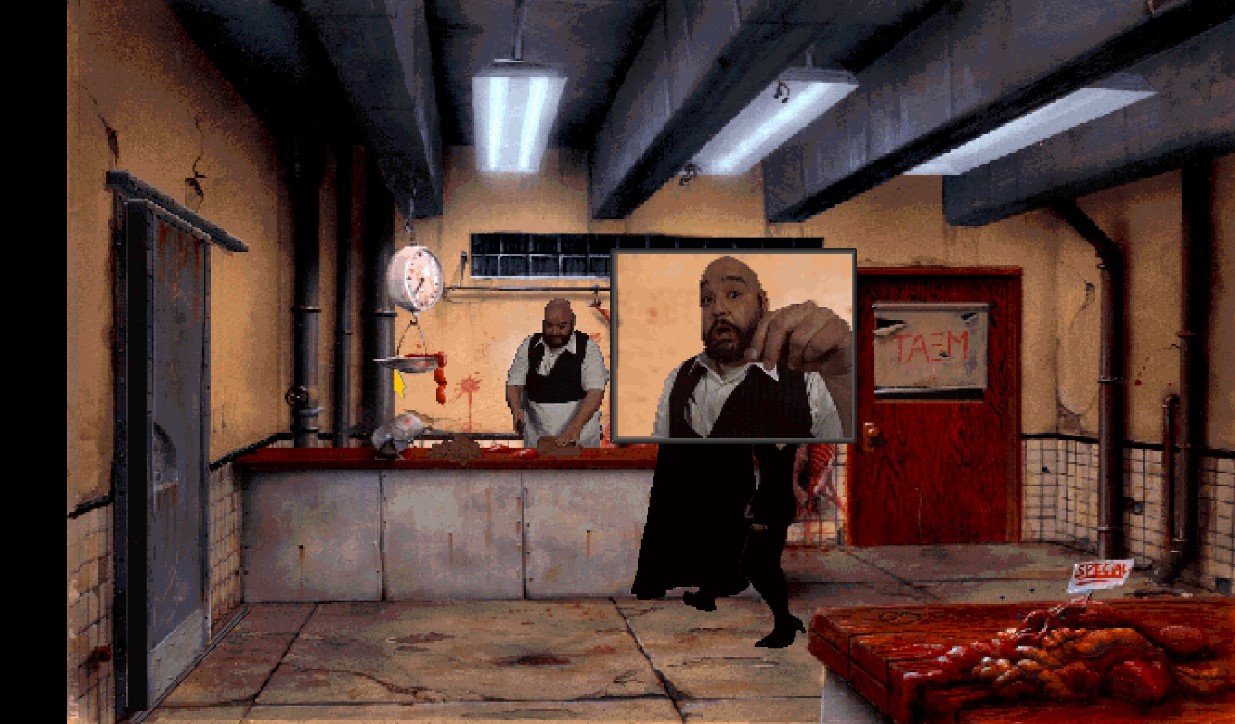

Early in the ’80s, I worked on many of Access Software’s products, including Beach Head II, the Tex Murphy graphic adventures, Links Golf, Countdown, and Echelon, to name a few. I formed Flashpoint Productions, a development studio, in the early ’90s and did products for EA (Noctropolis), Sega (Fred Couples Golf), and others. We began talks with Bethesda as a development studio and ended up finding a good match, and an acquisition followed. A bit later, I worked for Activision in their Innovation Lab and worked on some very interesting products around the Guitar Hero product line.

Erickson: I think I would have to say that I can probably narrow it down to two: the Tex Murphy series for Access and the Burnout Drag Racing series for Bethesda. The Tex Murphy series was designed by Chris Jones and me, and I did much of the programming. The concept was unique and fun and even included a flight simulator and video – both pretty novel at the time.

The Burnout products were something that I had to “sell” to Bethesda. Racing games were pretty new to them, and they didn’t understand the potential. Once I got the sign-off, the project took around 9 months to complete and was a full 6-degree-of-freedom physics model, a complete engine and chassis simulation – pretty unique at the time. It was a lot of fun to create, and the community that sprung up around it was amazing.

Erickson: When I was about 12, I was a sponsored BMX racer and spent a lot of time at our local bike shop. The shop had a few arcade machines, such as Space Invaders, Asteroids, and Red Baron. I got to play these a lot. I also had an early ColecoVision and Atari system at home. This was probably my first exposure to video games. My first programming exposure was, technically, with an electronics kit, but I also had a Timex Sinclair kit I built, and I was able to use the computer lab at a local university – this is where I really learned to program.

Erickson: Bethesda was a good company – a self-publishing company that was unique in its use of licensed products. Chris Weaver had ties in Hollywood that allowed him to secure some good licenses like Terminator and Gretzky. When I joined, there was a lot of effort being put into finishing up Arena (RPG) and several other projects were underway. My team helped with various parts of these and we also began development of some of our own. I enjoyed working with Chris (Weaver), Vlatko (Andonov), and the rest of the team in Maryland. Vlatko and I had many great adventures traveling around the world and meeting developers, distributors, and licensors. As Bethesda expanded, it got less personal and more business-focused by necessity.

Erickson: Originally it did. At Flashpoint, we had contemplated moving into publishing (and actually published one development utility). When we met with Bethesda, the system and philosophy they had in place were what we were looking for. We also had discussions with EA and others, but we wanted to have an influence on how our products were developed and produced. We felt like Bethesda was the right size and that this could still happen. Bethesda has changed a lot since then. In the 5 or 6 years I was there, it went from a smallish publisher to a multi-acquisition, investor-owned company. The philosophy was very different. It’s not good or bad, just different.

Erickson: The biggest differences are in scale and development tools. By scale, I mean the amount of assets that are generated. This isn’t to say there weren’t some big games back then (for example, Mean Streets had 3D data for key points along the West Coast of the U.S.), but the detail required for today’s graphic engines is much, much larger. For development tools, back in the day, we basically had a compiler (generally an assembler). There was no OS or libraries – you wrote everything yourself. Now, there are a wide variety of tools and libraries to support different platforms and features. The knowledge a programmer requires is not more about how to use tools and libraries as opposed to having to implement a multiple/divide function on a 6502.

Erickson: I guess the answer is yes and no. I think there are concepts in gaming that are accomplished in different ways based on the technology available. For example, the idea or root concept of a procedurally generated environment is not new; it was done in the late ’70s and early ’80s in games such as Elite, but the scale is quite different than what is done for No Man’s Sky. So I believe, to some extent, the design concepts have been around but are realized in different ways.

Erickson: It’s hard to pin one down for me. I tend to bounce around and try a variety of games. I still enjoy Forza and iRacing, but I also jump into a good shooter like Halo or Wolfenstein. I enjoy RPGs, but I have a hard time finding the time to invest in them. I am also a collector and fan of retro gaming. I have several emulation devices I picked up in China that are very portable, and I have a full set of emulators on my Steamdeck as well. It’s fun to see my old games being re-enjoyed in this way.

Erickson: I would still love to finish a drag racing game that I have been working sporadically on for many years. When I wrote the first one back in the 90s, there were limitations in technology that would not allow me to realize some of the design concepts I wanted (chassis dynamics and multiplayer are two of the big areas). Now technology is there, and I think it would be great fun to realize the vision.

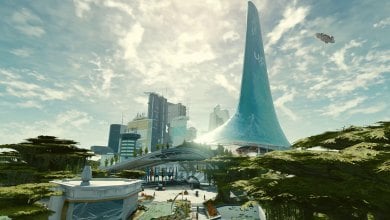

Erickson: I was part of the early work on the 10th Planet. Bruce (Nesmith) and Todd were working on the design, along with some input from Centropolis Entertainment. I was involved in a few of those meetings and some of the technology discussions. I was disappointed that it was not realized while I was there. The reason it was canceled is a bit fuzzy. I know part of it was due to Centropolis pulling back, as well as other project priorities in Bethesda. I don’t think it was actually formally “canceled” but just moved out of the priorities.

Erickson: I’m not sure which games Todd was referring to, but I know there were several games being talked about that never came about. There were a few with Centropolis, including Godzilla and StarGate (and others that I probably can’t mention since the movies were not made). We also were talking about a new Gretzky game and a new baseball game. There were also some discussions about expanding the Terminator products. So, a lot of concepts but limitations on team size, etc., limit what you can do.

Erickson: I try to keep tabs on some that I would consider friends or peers from the early days. Guys like Sid Meier, Will Wright, Dave Kaemmer (iRacing), Ron Gilbert, Louis Castle, etc.. It’s also been a lot of fun to follow people I worked with, hired, or mentored over the years, like Todd Howard, Guy Carver, Karthik Bala, Chris Jones, etc. Not all these people are “designers,” but all continue to have a hand in the games industry. I can’t really say that I follow games because of the “designer” any more than I watch a movie for the writer or director.

Erickson: It’s always a bit strange to hear of layoffs in an industry that appears to be doing really well. The gaming industry is no different. Companies are driven by sales and forecasts of sales, and if they don’t match with spending, the company takes proactive action to survive. I think there was a bit of over-hiring that occurred during COVID, and projections of market growth may have been exaggerated due to the rapid growth of gaming during COVID. I also think there is a bit of a “Pixar” model of hiring happening – this is where the company hires a bunch of people during the development of a project, and when that project is complete, the “excess” personnel are laid off (Pixar was notorious for this).

The closure of studios likely has other causes. When a studio is purchased, there is always a period of time when an attempt is made to merge the studio into the culture, systems, and processes of the company. This is a difficult task, at best, and often results in productivity, morale, and performance issues (accurate or not). I’ve experienced this firsthand with three of my companies – Access’ sale to Microsoft, Flashpoint’s sale to Bethesda, and Motion Software’s sale to ComCams.

Erickson: I actually still make games. I work on pet projects all the time. Sometimes, it’s just to play around with new technology or game engines or to explore a new technique I’ve read about. I really enjoy simulation and story games, so maybe there is a concept there that could be interesting.

Erickson: I was lucky to be a part of the birth of this industry, and it’s brought me a lot of joy. I’m glad I can still participate in some way and will as long as I am able.

We thank Brent for his time and valuable insights into the world of Bethesda. Among the many ideas the company considered making at one point, one that stands out is The 10th Planet, which Todd Howard recently brought up. It was canceled after several delays, but its concept of space exploration was used in Bethesda’s latest IP, Starfield.

Brent Erickson has a long history in the video game industry. Although he may not be as active as he used to be in his prime, his titles have undoubtedly inspired many new developers.

Thanks! Do share your feedback with us. ⚡

How can we make this post better? Your help would be appreciated. ✍